STATE CIRCLE

The Annapolis historic district is not laid out in the predictable and regular grid that many of us are accustomed to. As every tourist knows, the streets in the Annapolis Historic District are spaced unevenly and appear as if their irregular design is a byproduct of hundreds of years of changes and city growth. This is not the case. Annapolis' street plan was intentionally designed in 1696 as a conscious use of monumental architecture, planned vistas and ceremonial spaces, to make use of baroque planning principles. Archaeological excavations conducted around the State House Circle in the winter of 1989-1990, as part of remodeling and repaving of the traffic circle, uncovered intact deposits that dated to the 1720s. These deposits afforded Archaeology in Annapolis the opportunity to interpret changes in the historic district's layout. The historical interpretations resulting from the excavations illuminate issues concerning Annapolis' political organization and ideas of national citizenry throughout the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries.

Circles of Power

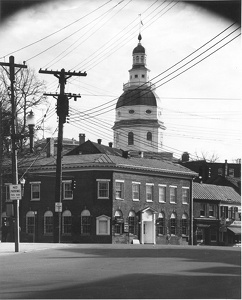

Crowning the historic district, the State House is ringed by a traffic circle on one of Annapolis's tallest hills-this is not by accident. In 1696 it was decided by the British monarchy that Maryland's capital was to move from St. Mary's City, then a Catholic stronghold, to Anne Arundel Town, a small Protestant city originally settled in 1649. Comprised of only a few streets, Anne Arundel Town was redesigned by Francis Nicholson, based on Baroque design principles originally developed during the Italian Renaissance. Renamed Annapolis in honor of England's Queen Anne, Nicholson superimposed his town plan on Annapolis' already existing streets, and created a new city comprised of two circles (State and Church), both with radiating streets stemming out from them. But why go through the trouble of laying out such an unusual town plan?

It appears as though Francis Nicholson followed the Baroque style used in the rebuilding of London in 1666 by Christopher Wren and John Evelyn. This particular style attempts to create visual illusions based on planned vistas, and convergent and divergent lines of sight culminating in monumental architecture, as a means of creating symbolically charged spaces. Along with joining Church and State circles by a single road to symbolize the recent union of British Church and State, Nicholson utilized a series of vistas made by using non-parallel lines of sight to create symbolic social order. Archaeological excavations conducted around State Circle in 1990 were able to determine that the sides of 5 of the 8 entries leading into State Circle broaden the closer they get to the State House, thus effectively creating divergent lines of sight that make the State House appear much larger than it actually is. This use of point perspective was later integrated into private landscapes of Annapolis elite such as Charles Carroll of Carrollton's garden.

Annapolis's baroque town plan was originally created as an embodiment of political power, attempting to naturalize the landscape's appearance as though it is one with the power that it supported. All of this was done during a time of civic unrest, directly after the official relocation of the capital from St. Mary's City. This raises an intriguing question: how did Annapolis change after the American Revolution-when a particularly difficult period of civic unrest had recently ended?

Citizenry and Symbolic Power

It appears as though there is a meaningful connection between the Baroque town planning in Annapolis and the ideas of newly formed American nationalism in the Federalist period, from 1780-1820. In the 1780s the State of Maryland replaced the State House's older cupola with an eight-sided multistoried dome. On the eight sides, four ranks of windows on each of the different stories were situated to look down on each of State Circle's radiating streets and paths. Because of its many tiered windows that can be seen all over town, the cupola acts like a viewing platform, or panopticon. The idea of the panopticon plays off Federal period ideas for citizens both to see and be seen. Panoptic designs, and the social theory that underlay them, were commonly used throughout society, and can be seen in homes, hospitals, churches, insane asylums, and schools. The 1780s State House cupola represents a new notion for establishing social control, both on the body and in the mind. Based on the Federalist idea of a franchised citizen, a participatory citizen- rather than a passive subject, the State House as panopticon sought to ensure correct social behavior by newly independent Annapolitans.

Throughout the 18th century Annapolis consistently utilized aspects of social control, seen in both Nicholson's Baroque town plan and the Federal period State House cupola. Formed at times of civic unrest, these parts of the urban landscape have created Annapolis as a political volume. With the use of new and inventive forms of archaeological analysis, Archaeology in Annapolis has begun to more fully understand the extent to which the 18th century builders of Annapolis used the urban landscape as a tool in which to create and maintain social control.

Further Reading

Leone, Mark P.

1995 A Historical Archaeology of Capitalism. American Anthropologist 97:2:251-268.

Leone, Mark P., Jennifer Stabler, Anna-Marie Burlaga

1998 A Street Plan for Hierarchy in Annapolis: An Analysis of State Circle as a Geometric Form. In

Annapolis Pasts: Historical Archaeology in Annapolis, Maryland, edited by Paul A. Shackel, Paul R.

Mullins and Mark S. Warner, pp.291-306. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Leone, Mark P. and Silas D. Hurry

1998 Seeing: The Power of Town Planning in the Chesapeake. Historical Archaeology 32(4):34-62.

Read, Esther Doyle

1990 "Archaeological Investigations around State Circle in Annapolis, Maryland."

Shackel, Paul A., Joseph W. Hopkins and Eileen Williams

1988 "Excavations at the State House Inn, 18AP42, State Circle, Annapolis, Maryland. A Final

Report." on file: Maryland Historical Trust Crownsville, Maryland, and Historic Annapolis

Foundation, Annapolis.

Stabler, Jennifer

1990 "Archaeological Investigation of the State Circle Public Well, 18AP61." on file: Maryland

Historical Trust, Crownsville, Maryland and the Historic Annapolis Foundation.